I’ve received several emails asking about the differences between focus stacking and shooting with a tilt/shift lens. Here’s the short answer: these are two very distinct techniques. Focus stacking is a means of gaining sharp depth of focus (more near-to-far sharpness in the photo) while shooting at prime apertures. Focus stacking can be done using any lens. On the other hand, a tilt/shift lens is a specialized fixed focal length lens that permits changing where the plane of focus is positioned. Nikon, for example, offers 19mm, 24mm, 45mm, and 85mm tilt/shift lenses.

To do focus stacking you take several images with your camera mounted on a tripod, all at the exact same exposure, but at different focus distances into the frame. These shots must then be combined using software (my choice is Helicon Focus as it has a RAW IN – DNG OUT mode). You’re basically getting a lot more depth of field, a lot more of the scene in focus, without resorting to small apertures and the resulting diffraction problems. But, as always, there is a catch…or I should say, several catches. The first is subject movement from frame to frame. Software can fix some minor movement problems, but try photographing on a windy day and you’ll end up with a blurry stack. Another problem happens when you have one frame with a close in-focus object positioned against a distant out-of-focus background, which has to stack with the reverse, the close object now out-of-focus but with an in-focus background. The resulting stacked image often shows an obvious halo around that close object. Focus stacking works best where there is a smooth transition of the subject you want sharp in the final composite image. Just in passing, both Helicon Focus and Zerene Stacker, the two most popular focus stacking software programs, yield much better results that does Photoshop’s “auto-align, auto-blend” option.

Tilt/shift lenses do not give you more depth of field. As I said above, they allow you to reposition the plane of focus. And they are expensive. Nikon’s 19mm, while a superb lens, is about the same price at a D850 body. But using tilts means you can fight the wind, to get the shot in one frame rather than trying to put together several frames. Use a tilt to position the plane of focus across a field of flowers, and a medium aperture works to cover the entire scene. There is no software option that duplicates what a tilt movement does in a single frame. As to shift — sliding the lens left-right or up-down — this effect can be accomplished in software by warping or distorting an image, but with the result of stretched pixels and the need to crop off part of the original image capture. No big deal if you keep the resulting image small but certainly noticeable in a large print. Tilt/shift lenses also allow you to use both tilt and shift simultaneously; the newer t/s lenses allow these movements to be in the same axis or at 90 degrees to each other. As always, what’s best depends on your style of shooting, your subject matter (architectural work almost demands using a shift to avoid keystoning), and what you want to do with your images.

My quick advice is to stick with focus stacking, or at least until you can verbalize a concrete reason to purchase a tilt/shift lens. However, if you have GAS (Gear Acquisition Syndrome) and some expendable income I can easily imagine a tilt/shift lens in your future.

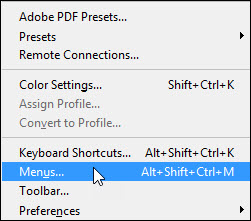

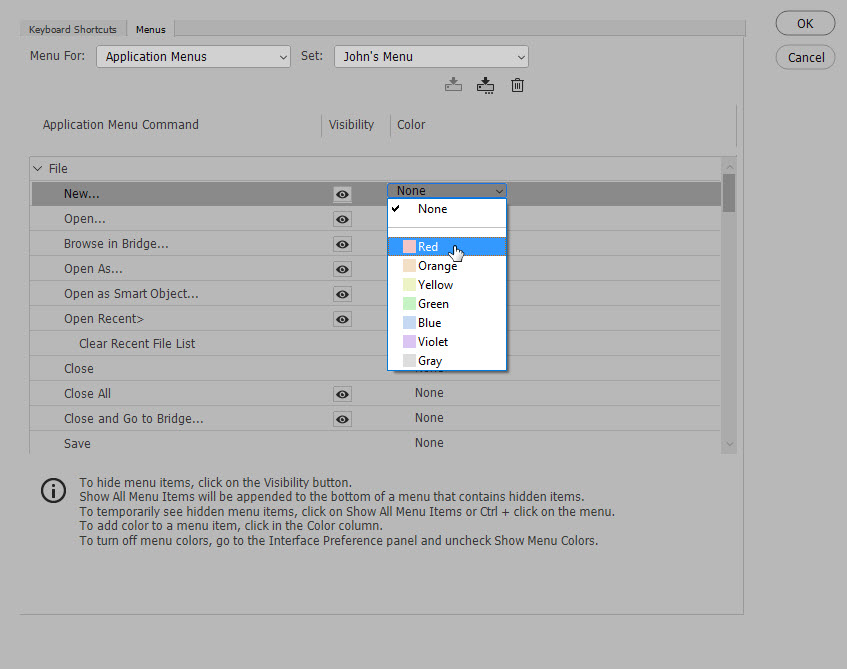

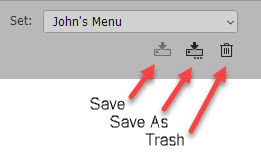

You can see that I saved my choices as “John’s Menu.” You can switch back to the original Photoshop version at any time by selecting “Photoshop Defaults” in the “Set” drop down. You can make as many custom menus as you want, although I don’t know why one would do this. To delete a custom menu, select it in “Set” and then click the trash icon.

You can see that I saved my choices as “John’s Menu.” You can switch back to the original Photoshop version at any time by selecting “Photoshop Defaults” in the “Set” drop down. You can make as many custom menus as you want, although I don’t know why one would do this. To delete a custom menu, select it in “Set” and then click the trash icon.

NIKON D850 LENS PROFILE PROBLEM?

Recently I was doing some night sky photos using my D850 and the Nikon 20mm f/1.8. When I looked at the shots in Lightroom I noticed something odd: in the darker areas, especially toward the corners of the frame, a series of faint concentric rings were visible, apparently emanating from the center of the image. I did not have any sort of filter on the lens, so this could not be some sort of interference pattern. What was happening?

I started doing a lot of testing. I finally discovered that these “rings” would disappear if I unchecked the “lens profile correction” in the Lens Corrections tab in Lightroom’s Develop module.

Was this a bad lens profile or what? I considered some options:

What on earth was going on here? Was this a problem specific to the D850?

Now totally frustrated, I looked at my Develop settings in Lightroom. If sure would be great to be able to use those lens profile corrections to solve the distortion and vignetting problems that all wide angle lenses have. I discovered that if I set the sharpening Amount slider to zero the rings disappeared, but in my normal RAW file workflow I generally do want to apply some sharpening. Back at the Lens Profile tab, I left the “profile correction” on, but pulled the sliders for Distortion and Vignetting at the bottom of that tab to zero, effectively negating the profile. Sure enough, the rings disappeared. But wait…how about separating those two sliders, adjusting one but not the other? The culprit seemed to be the Distortion slider. I could have the Vignetting slider all the way to the right, as high as possible, but the moment I moved the Distortion slider from the zero position the rings started to show.

As I stated earlier, I’ve only seen this in very low light shots, and haven’t tried any tests with longer focal lengths. Has anyone else shooting with a D850 seen similar results? Right now I’m thinking that when I’m processing images taken with the D850 in very low light I will leave lens profile correction turned on, but pull that Distortion slider to the far left before slowly moving it to the right.