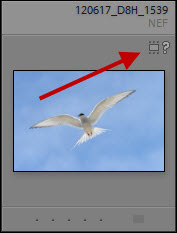

Shortly after the Tucson workshop, I traveled to Fairbanks, Alaska, to photograph the aurora borealis, the northern lights. The last time I shot the aurora I was using film…digital cameras were still in there infancy. And what a difference digital makes! On this trip I used both my Nikon D4 and D800E, at shutter speeds between 6 and 20 seconds with the 14-24mm and 24-70mm lenses wide open at f/2.8, and ISOs of 1600, 2200, and 3200.